PAUSE for Pedagogy

A Heart Surgeon's Journey to the Power of 3: Servant Leadership, Followership, and Clinical Management

By Christopher C. Phillips

Christopher C. Phillips, M.D., M.B.A., C.P.E., F.A.C.S., F.C.C.P., F.A.C.C.

Christopher C. Phillips, M.D., M.B.A., C.P.E., F.A.C.S., F.C.C.P., F.A.C.C.

Since childhood, I have been driven to follow a career in medicine. And so, I became a medical doctor (M.D.) at Ross University School of Medicine and pursued general surgery at the University at Buffalo in New York. I completed my cardiovascular & thoracic surgery fellowship at Indiana University in Indianapolis, Indiana. Once I was in clinical practice as a cardiovascular & thoracic surgeon, I became a certified physician executive (C.P.E.) through the American Association for Physician Leadership (A.A.P.L.) program. During my work in the C.P.E. program, I knew I wanted to continue my education. I then pursued and graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst with a Master of Business Administration with a concentration in Medical Management. At present, I am the Chief Cardiovascular Surgeon and Medical Director of Clinical Quality at Beaumont Hospital in Troy, MI. I am also an Associate Professor at Oakland University's William Beaumont School of Medicine & Health Sciences. I have worked for large institutions, Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, OH, and small hospitals like Trinity Health in Minot, ND. Regardless of the institution's size, there is an opportunity for healthcare teams to work together to achieve great things for our patients and their families and friends.

"It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye." - Antoine de Saint Exupéry, The Little Prince (p. 87)

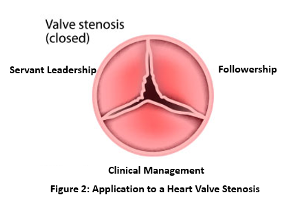

As a medical professional, there are powers of 3 that readily come to mind. The average human body can survive 3 minutes without oxygen, 3 days without water, and 3 weeks without food. The tricuspid, aortic, and pulmonary valves — 3 of the heart valves — have 3 leaflets that allow them to function normally. I have learned on my journey to carry the power of 3 into my approach to leading and managing cardiovascular service lines: servant leadership, followership, and clinical management.

In the early stages of my professional development as a medical student, the need for leadership did not present in my curriculum nor at the forefront of my mind. Instead, I focused on learning medicine, constantly challenging myself in anatomy, and becoming a medical doctor. As a result, I did not appreciate the need to develop and sustain leadership competencies. Looking back, I have been on an evolutionary leadership journey in medicine ever since. First, I focused on clinical components, then on leadership competency with a fusion of management perspectives. I like to use a normal heart valve (see Figure 1) to visualize what I’ve learned and to support stakeholders to realize change. My evolution in learning and applying the principles of servant leadership, followership, and clinical management contributed to the small rural hospital I worked at in Minot, North Dakota being selected as a Truven Health Analytics Top Cardiovascular Programs in the Nation in 2013 – a truly monumental achievement for a community hospital.

But this evolution took time. In the beginning, I was not the most successful in working to bring people together to accomplish particular goals. Metaphorically, there was a stenosis that weakened the valve (see Figure 2) – namely, my understanding of the leadership system. What could I do to fix the stenosis? If I were in surgery, I would work diligently to repair the valve; if repairing wasn’t an option, I would replace it.

I approached my leadership challenge as I would surgery; I knew there was a “stenosis,” but how could I facilitate change so I could limit any weaknesses? I began to research leadership concepts in healthcare and came across the American Association for Physician Leadership – whose President, Dr. Peter B. Angood, was a plenary speaker at ILA’s Healthcare Leadership conference this year. As I continued my research, I started to understand and appreciate more of the fundamental dynamics at play within healthcare, specifically cardiovascular surgery in hospital settings. I also realized there was a lot more to learn, so I decided to pursue advanced education to become a certified physician executive (C.P.E.). Through my course work, I began learning about various forms of leadership and critical concepts that I needed to understand, manage, or mitigate to be successful. I knew stakeholder management and communications were necessary, and I soon realized how interdependent these concepts were. For example, I could have an excellent surgery; however, if others were unaware of what needed to transpire once the patient left the operating room (OR), the patient's wellbeing could be impacted.

I began to think about leadership more organically and consider what it meant within my cardiovascular and thoracic surgery world. As I delved into more research, Robert Greenleaf's concept of "servant leadership" spoke to me. Yes, spoke to me. It was surprising to me that I, a well-trained surgeon, found myself being drawn into this conceptual world of leadership.

Later, during my M.B.A. program, servant leadership once again came up in discussion. One of Greenleaf's quotes (1998) was quite poignant to me: "One cannot be hopeful, it seems to me, unless one accepts and believes that one can live productively in the world as it is-striving, violent, unjust, as well as beautiful, caring, and supportive" (p. 21). This quote strengthened my belief in servant leadership and led me to strive to become that servant leader. I always try to put others first, as Blanchard (2019) writes, and I seek to find what others need to succeed, whether they are staff in my office, team members in the OR, professionals who deliver post-operative care, or patients themselves.

I put my new found understanding and commitment into practice in how I approached change in my organization. One example involved my vision to have physician assistants (PAs) provide surgical and medical care to improve outcomes while reducing costs. Our PAs were comfortable and competent in the performance of their day-to-day procedures, but I knew many had the capability and knowledge from prior training and experience to deliver more advanced medical care. Upon presenting my vision to the team, I encountered resistance at first. The PAs were concerned about increasing their workload, the liability of the change in care model, and other potential issues. I took each of their points and worked with them to gain a different perspective on alternative options that would offset their concerns. I integrated their feedback and gained their buy-in by formulating new processes and procedures that allowed them to become comfortable with the medical management component of the practice. I also worked with key administrators to bring these changes to the implementation of our future state of operations. If I had forced this concept onto the PA group, I would have disrupted the service line and morale would have suffered. Instead, we effectively changed our strategy by balancing servant leadership with followership and clinical management. The change was for the better, and there was more balance amongst the various groups of people. Of course, not everything was perfect or harmonious, but mindsets were shifted.

Understanding followership in healthcare settings is important. As Leung et al., point out, “followers represent at least 80% of the healthcare workforce [1] and there is increasingly less emphasis on hierarchical leadership [2]" (p. 99). Despite these numbers, "Organizations invest 80% of their development resources towards the leadership… a mere 20% is dedicated to enhancing the skill of the followers" (Cendán & Simms-Cendán, 2018, para. 3). With this in mind, I continually explore followership within the service line to help drive change. I think of leaders through one lens, and through another lens, I witness the constructs of followership. I believe that "Good followership is characterized by active participation in the pursuit of organizational goals" (Eagle's Flight, 2022, para. 3).

In another example, I worked with the advanced practice providers (APP) to help build clinical pathways and manage their roll-out. This allowed us to improve two key metrics that we needed to improve upon — early extubation times and tighter control of post-op blood sugars. I wanted the APPs to drive the change and come to me with any resistance they came up against, so we could brainstorm our next steps together. I needed to allow them to manage their processes and I needed to trust in their abilities and capabilities. Their performance demonstrated the positive outcome of their efforts.

During my time in Minot, I worked closely with my teams — OR, nursing, specialty physicians, and administrators — to implement cardiovascular & thoracic surgical service line changes. We worked to ensure that our expectations met perceptions related to clinical outcomes and cost containment regarding cardiovascular & thoracic surgical care. By defining each team member's role, we identified the difference between how they envisioned their role and participation versus my perception. As a result, we utilized team members' responsibilities as a resource to help deliver cost-effective care in the most efficient ways.

While the team realized the hospital's positive outcomes, we were unaware that our work would be in the national spotlight. When we were named a Truven Health Analytics Top Cardiovascular Programs in the Nation in 2013, we were one of 15 community hospitals to receive this prestigious national award. I believed in our work, so I decided to share our insights with others. I wanted other healthcare leaders to see how you could enact change without a costly investment or capital expenditure. Once our program obtained the national award, I submitted casework to an awards program sponsored by Dorland Health. As a result, I won the 2013 Medical Director award for the Case in Point Platinum Awards, which I proudly accepted on behalf of the team. We successfully flipped the script and reframed our approach by leaning heavily into servant leadership and followership intimately paired with clinical management.

At present, I am the Chief Cardiovascular Surgeon of Beaumont Health – Troy, Michigan, and Medical Director of Clinical Quality. This hospital is a much larger hospital system than I worked with in Minot. Nonetheless, I leverage the same methodology as discussed throughout this article. Through this approach, this institution also received national recognition. Beaumont Health – Troy, Michigan made the list of Watson Health Top 50 Cardiovascular Hospitals for 2022. The success lies within the team and our people who have allowed us to accomplish these remarkable outcomes and betterment for our patients.

It is not just in the hospital that I have put my newfound insights into practice. I have also been an Associate Professor at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine & Health Sciences and at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine & Health Sciences. In these roles, I consciously inject the concept of leadership and followership into medical students and residents. Clinical knowledge is critical; however, I also recognize the importance of greater awareness of leadership systems. Therefore, I share my perspectives and experiences to begin encouraging the growth and development of these critical topics for them.

If nothing else, I try to impart to them the following building blocks, which I believe contributes to the ability of individuals to pivot within their role as leaders or followers:

- Appreciate each person is on their journey

- Build self-awareness by developing one's emotional and social intelligence

- Understand your audience and formulate your delivery

- Recognize the job is never done; expect setbacks and a return to the prior behaviors

- Instill a pro-active team approach versus being reactive

I’ve learned over the years that a fusion of servant leadership, followership, and clinical management must be at the forefront of decision-making. There must be a balance across these dimensions in healthcare. The key is to keep our end goal in mind — being the best we can be for our patients, their families, and friends. Success is not based on the institution's size, structure, or reputation; instead, it is based on the people, on individuals working together for a common goal. I encourage everyone in a leadership role to include a knowledge of followership in their practice. An easy first step is to simply acknowledge their team members’ contributions, commitment, and demonstrated successes while also supporting their aspirations.

References

Blanchard, K. H. (2019). Leading at a Higher Level: Blanchard on Leadership and Creating High Performing Organizations. Pearson Education, Inc.

Cendán, J. C., & Simms-Cendán, J. S. (2018). Wanted. Annals of Surgery, 267(4), 619–620. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002510

De Saint-Exupéry, A. (1988). The Little Prince (K. Woods, Trans.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. (1943)

Eagle's Flight. (2022, February 25). Followership in Leadership: The Role It Plays. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.eaglesflight.com/resource/followership-in-leadership-the-role-it-plays/

Greenleaf, R. K., & Spears, L. C. (1998). The Power of Servant-Leadership: Essays. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Leung, C., Lucas, A., Brindley, P., Anderson, S., Park, J., Vergis, A., & Gillman, L. M. (2018). Followership: A Review of the Literature in Healthcare and Beyond. Journal of Critical Care, 46, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.05.001