Intentional Leadership: Getting to the Heart of the Matter

Intentional Leadership: Getting to the Heart of the Matter

by Stan Amaladas

Stan Amaladas is a Research Associate and Lecturer at the University of Manitoba, the University of Winnipeg, Okanagan College – Kelowna, British Columbia, and co-editor of Peace Leadership: A Quest for Connectedness.

Stan Amaladas is a Research Associate and Lecturer at the University of Manitoba, the University of Winnipeg, Okanagan College – Kelowna, British Columbia, and co-editor of Peace Leadership: A Quest for Connectedness.

What’s It About?

In his Foreword to my book, Intentional Leadership: Getting to the Heart of the Matter, Ray Becvar wrote: “Every book is a story.” And, I would add, every story has a context. The context for this book and story is violence, reactions to violence, and the storied choices of 11 men and women who intentionally chose to terminate endless cycles of violence for the sake of real change. Cycles without end are precisely what the name implies. They are, as Watzlawick, Weakland, & Fisch (1974) noted, “endless in the sense that they contain no provision for their own termination” (p. 22). Termination is not part of the ‘endless’ vocabulary. Termination is meta to endless cycles and is of a different logical type from within the rules of violence and counter-violence. The stories of these 11 men and women illustrate (a) their capacity to step beyond their socialized narratives, and, by implication, to terminate the endless cycles of violence and counter violence, (b) their courage to act on behalf of the possibility that they can initiate a new beginning even when they experienced the irreversible consequences of the destructive actions of others in their own lives.

I define these individuals as leaders by intention.

Why Is Intentional Leadership Needed Today?

As James Patrick Kinney (see Hawkins, 2012) wrote about five decades ago, our storied violence-revenge reactions, and our inability to begin anew or tell a new story, continue to bear witness that we, as individuals, as organizations, as societies, and as nations, are “dying from the cold within.” The refusal to let go of old identities, the arrogant claims for racial or religious superiority, indiscriminate violence, and vengeful reactions, and building relationship solely from the perspective of exchange, continue to contribute to this tragic reality. Does it have to remain this way?

One stellar example that it does not have to remain this way was the graceful response of families whose loved ones were murdered in Charleston, North Carolina, June 17, 2015. Their act of grace lay in their choosing to forgive the gunman, even though the gunman himself did not ask for forgiveness. They chose to forgive the unforgivable. While the white gunman thought that he could eliminate his racist sentiments by eliminating his objects of hatred, while he intended to start a race war, the family members sought instead to eliminate racism by choosing to relate to the irreversible consequences of this gunman’s actions with forgiveness. In doing so, these family members effectively stripped others away from their dominant violence-counter-violence discussions and reactions. They terminated any intention to start a race war. Their human act of forgiveness opened instead, a space for a new, different, and hopeful conversation – as a possibility.

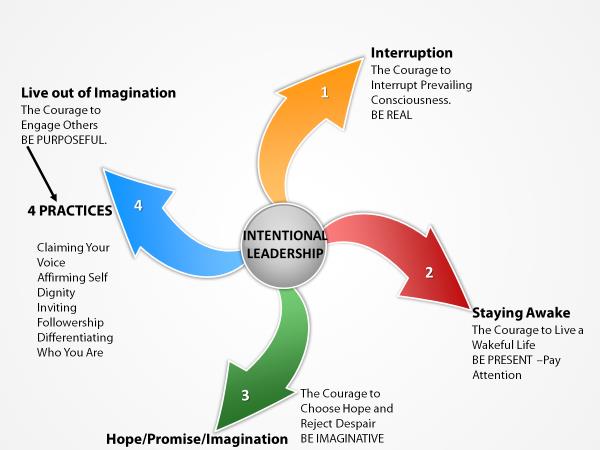

Four Critical Activities of Intentional Leadership

First, intentional leaders are real. They are acutely aware of all that is tugging for their attention, and they not afraid to interrupt the prevailing consciousness of their followers for the sake of focusing on what is essential and important. Pope Francis is one example of a leader who is not afraid to interrupt the comfort zones of his followers (members of the Catholic Church) and his own internal leadership team. He challenges his own leadership team to ask questions about the gap between the espoused and actual state of the churches they lead, to resist living a double life (existential schizophrenia), and to challenge everything that might make them closed in on themselves. Within the context of his organization, the Catholic Church, Pope Francis deliberately invites his followers to terminate their focus from one that is comfort-centered, self-focused, and internally closed, to one that is mission-centered with a relationship that allows them to be influenced by a personal encounter with their ultimate spiritual leader, Jesus Christ. At the same time, as their leader, Pope Francis is fully aware that the changes that he wants to bring about in his organization cannot simply occur by dictum, but rather by a real change of heart. The latter is not under his control. Herein lies a limit to the work of intentional leadership as opposed to the ‘dictums’ imposed by rulership.

Second, intentional leaders are present. Like Jean Jacques Rousseau, a 19th century social analyst, they call their followers to wake up to the challenge of leading deliberately while in the middle of “a perpetual clash of cliques and factions,” where “each person is mindful of his own interest,” and “no one of the common good” (Rousseau, 1776/1997, pp. 191- 192). Pushing this idea of leading with intention to the extremes, I explore the challenge of purposeful action in my book through the stories of four men and women, described below, who, when confronted with the irreversible consequences of the violent actions of others and of life (illness), made choices “to serve the evolution of life” (Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, & Flowers, 2008, p. 11) in ways that are exemplary of the best of what life has to offer.

Robert Waisman (1931-present), a Canadian, was thrown into a Nazi concentration camp in Buchenwald at the young age of 10 for no other reason than being a Jew. For 30 years after his liberation, Waisman remained silent about his experience. Today, he is speaking about his experiences and offering a light of hope to bring healing to all others who have endured suffering through forgiveness, compassion, and understanding. What triggered the breaking of his silence? What woke him up? What is the place of forgiveness in the face of the unforgivable or in the face of others who have not asked for forgiveness?

Victor Frankl (1905- 1997), was also thrown into a Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz, 1944-1945, for no other reason than being a Jew. While in his unforgivable condition, Frankl refused to give up what he defined as the last of human freedoms, namely, the power “to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way” (Frankl, 1984, p. 86). What enabled Frankl to wake up to the opportunity to make use of his situation to focus on “the moral values that a difficult situation may afford him” (Frankl, 1984, p. 88)?

Jimmy Greene (1975- present), is a music professor at Western Connecticut State University (WCSU). Four months after Greene moved his family to Newtown, Connecticut, from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to teach at WCSU, his daughter, Ana, who was only “six and a half, as she would always emphasize to her parents” (CBS News, 2016), was one of 20 children who were murdered by a gunman at Sandy Hook Elementary School on December 14, 2012. In the face of yet another unforgivable act, her father did not give in to anger, resentment, and revenge, but chose instead to stay awake to the possibility of honoring and celebrating his daughter’s life by composing and producing a CD, A Beautiful Life. What enabled him to choose the celebration of life?

Lauren Hill (1995-2016), an aspiring basketball player, was on her way to “greatness with a collegiate basketball scholarship when she got the news that she had an inoperable brain tumour that left her with a maximum of two years left to live” (ABC News, 2015). The world or (normal) life as Lauren may have known it, stopped on the day she was exposed to the vulnerability of being dealt a bad hand (inoperable brain tumour). Rather than giving up, she showed up regularly for her 6am basketball practices at Mount St. Joseph, a Division lll school in suburban Cincinnati. On June 11, 2016, Lauren received the first "For the Love of the Game" award presented by the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame. This award is presented for showing outstanding courage and inspiration. Hill’s example is a way of celebrating the many lives of people whom you may know, who continue (intentionally) to hold the candle of never giving up when confronted with their own physical ailments. What enabled her choice to teach others how to live in the moment?

Third, intentional leaders are imaginative. Like the former President of the United States of America, Barack Hussein Obama, intentional leaders risk imagining and beginning something new. The question that lies in front of us in times or violence and uncertainty is: How can we lead well while in the middle of the certainty of uncertainty without losing hope? When confronted with the uncertainty and unpredictability of the future, three consistent themes appear to dominate the consciousness of Barack Obama: hope, imagination, and promise. Throughout his tenure, Obama’s spirit of hope called on his followers not to deny the diagnosis of their time, not to deny reality, but to fiercely deny the verdict that follows such a diagnosis. These, among other things, include denying the verdict that there will be no place in America for a "skinny kid with a funny name," or that the slaves will always be slaves, or that immigrants will not find America to be a better place. This was the internal resolve that he brought to his followers (Obama, 2004).

Fourth, intentional leaders act out of their imagination. As exemplified by the stories below, they imagine that there can be a new beginning and thereby open all to the possibility of writing and telling a new story, rather than surrendering to the real conditions and real consequences of their times, rather than being imprisoned by their old stories.

Betty Ford (1918-2011), First Lady of the United States of America from 1974-1979, claimed her voice while in the middle of her internal struggles with alcohol and breast cancer, and the voices of women who were excluded from mainstream society based on what she termed “emotional ideas about what women can do and should do” (Ford, 1975, Para. 6).

Rosa Parks (1913-2005), a mother of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, not only refused to surrender her seat to a white person for the sake of affirming her dignity as a person, but also dared to ask the question: “Why do you all push us around?” In the midst of injustice, she chose to engage the other in a conversation. The answer she received was: “I don’t know, but the law is the law and you’re under arrest” (Taylor, 2015). This section focuses on both her decision to say NO to injustice, and the relationship between knowing (or not knowing) and doing.

Jesus of Nazareth (0 – 33). At the risk of appearing parochial, I selected the story of Jesus of Nazareth because of his audacity to publicly invite followership. For our purposes, inviting followership is not a religious, but a human act. With the context of endless cycles of violence-revenge, he was also selected because of his determination to break from the old [“You have learnt how it was said: You must love your neighbor and hate your enemies”] and initiate something new [“But I say this to you: love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you”] (Matthew, 5:43-44). What kind of followership was he inviting? What are the limits of inviting followership? What was it about his invitation that also moved many to withdraw from him and reject his invitation (John, 6:66)?

Lee Kuan Yew (1923 – 2015), former Prime Minister of Singapore and founder of modern Singapore, had an intentional response of differentiation when “independence was thrust” upon his nation. (Lee, 1965, 2009). Singapore was expelled from the newly formed Malaysia in 1965. This section focuses on his intentional leadership in inviting Singaporeans to both stand their ground and, at the same time, be open to others, including those who told him to “get out” of Malaysia, as he engaged his population in an unenviable process of building a nation out of a polyglot collection of migrants from China, India, Malaysia, Indonesia and several other parts of Asia. He did not surrender to the idea that an independent Singapore was simply not viable.

Figure 1: Four Critical Activities of Intentional Leadership

Continuing the Leadership Conversation of Changing Hearts

Recall for instance, Burns (1978), when he talked about the “leader’s fundamental act,” namely, “to induce people to be aware or conscious of what they feel… (so) that they can be moved to purposeful action” (p. 44). He quotes Susanne Langer in saying: “where nothing is felt, nothing matters” (p. 44). Intentional leadership then, is about how leaders and followers are moved to purposeful action; they get to the heart of the matter by acknowledging that if nothing is felt in one’s heart, there will be no real change. Can we teach ourselves and others to feel the need to change our (their) hearts from, for example, hate to love? Nelson Mandela (1995) would say Yes! Beginning with the belief that “deep down in every human heart there is mercy and generosity” (p. 622), he would continue to say: “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love…” (p. 622).

An Educative Strategy

For the sake of changing hearts, Intentional Leadership: Getting to the Heart of the Matter offers a deutero-learning framework from Bateson and Bateson’s (1987) perspectives of “learning to learn” and “character change due to experience.” It goes beyond what Lord and Hall (2005) defined as “surface approaches” (Lord & Hall, 2005, p. 592) to both leader development and leadership development. While surface approaches tend to focus more on the development of behavioral styles and skills acquisition, the deuteron-learning model focuses instead on “the deeper, principled aspects of leadership…” (Lord & Hall, 2005, p. 592).

From the perspective of “learning to learn,” (meta-cognition) deutero-learning dwells in constructing learning and conversational spaces where both leaders and followers learn to see how they are a part of the system in which they are participating, and how what they do while in their system continues to perpetuate and maintain their system, their realities, their identity, and their character. This learning process, however, is tricky in the sense that there is no guarantee that all hearts will change; there is no guarantee that all hearts will want to change; and there is no guarantee that some won't master instead, the art of pretend change.

At the same time, the intent of deutero-learning is to move learners in the direction of knowing their worlds differently; of opening spaces for telling new stories and changing hearts. Within the context of the violence or our times, one learning that is particularly relevant to the work of intentional leadership is deeply connected to Thoreau’s “infinite expectation of the dawn” (Thoreau, 1995, p. 59). “We must learn,” he said, “to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep” (Thoreau, 1995, p. 59). Especially in times of violence, imagine a world that chooses not to reawaken itself to the dawn of a new day or to the expectation of dawn.

References

ABC News. Espy Awards: Remembering Lauren Hill [Video file]. (July 15, 2015). Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/video/espy-awards-remembering-lauren-hill-32481418

Bateson, G. & Bateson, M.C. (1987). Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

CBS News (January 15, 2016). Newton's Dad's Album Honoring Daughter Earns Grammy Nominations. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/sandy-hook-victim-dad-jimmy-greene-nominated-two-grammys-jazz-album-inspired-daughter/

Ford, B. (1975). First Lady Betty Ford's Remarks to the International Women's Year Conference, Cleveland, Ohio [Transcript]. Delivered on October 25, 1975. Retrieved from https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/bbfspeeches/751025.asp

Frankl, V.E. (1984). Man's Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Washington Square Press.

Hawkins, S. (2012). "The Cold Within" James Patrick Kinney: Poem. Purpose. Progress. All Things If. Retrieved from http://www.allthingsif.org/archives/1405

Lee, K.Y. (1965). Transcript of the Speech by the Prime Minister Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, in English at the Serangoon Gardens Circus on Saturday, 11th December, 1965. Retrieved from http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/lky19651211c.pdf

Lee, K.Y. (2009). Speech by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Minister Mentor, at the S. Rajaratnam Lecture, 09 April 2009, 5:30 pm at Shangri-La Hotel. Retrieved from http://www.pmo.gov.sg/mediacentre/speech-mr-lee-kuan-yew-minister-mentor-s-rajaratnam-lecture-09-april-2009-530-pm-shangri

Lord, R.G., & Hall R.J. (2005). Identity, Deep Structure and the Development of Leadership Skill. The Leadership Quarterly 16, 591-615.

Mandela, N. (1995). Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Obama, B. (July 27, 2004). Keynote at the Democratic National Convention in Boston, Massachusetts [Transcript]. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A19751-2004Jul27.html

Rousseau, J.J. (1997). Julie, or the New Heloise: Letters of Two Lovers Who Live in a Small Town at the Foot of the Alps. In The Collected Writings of Rousseau, Vol. 6, (P. Stewart & J. Vache, Trans.). Hanover: University Press of New England. (Original work published in 1761).

Senge, P., Scharmer, O., Jaworski, J., & Flowers, B.S. (2008). Presence: Human Purpose and the Field of the Future. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Taylor, Justin. (December 1, 2015). 5 Myths About Rosa Parks. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from

http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/ct-rosa-parks-myths-20151201-story.html

Thoreau, H.D. (1995). Walden: Or Life in the Woods. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J., & Fisch, R. (1974). Change: Principles of Problem Formulation and Problem Resolution. New York, NY: WW. Norton & Company.